The most important aspects of conditioning for womens football

As we have discussed elsewhere, there are 2 main schools of thought out there when it comes to females and physical activity, or more specifically when it comes to females and preparing via strength and conditioning for physical activity, or merely just strength and conditioning as an end in itself. There is one school of thought that believes that women are different to men and therefore must train completely different, and in some extreme cases shouldn’t even be doing strength and power related training at all. Then there is the other school of thought which lies down the opposite end of the spectrum, and believes that this is nonsense, and that despite some differences between the 2 genders, there is enough similarity for training to be exactly the same for women as men – especially when it comes to strength training, because strength training benefits everyone. And also as with most things with 2 extremes, the truth, or the reality, lies somewhere in the middle.

‘Constructing a plan for female athletes requires special considerations. Males and females have definite biological differences in terms of strength and body composition.’

‘In program design, the gender of the athlete is important. Female athletes have different needs than male athletes, which will affect the training plan. Strength training is a more significant part of training for female athletes during all phases of the training year.’

Vern Gambetta

In short, structurally and functionally there are a lot of similarities, and by and large, training practices for the 2 can be very similar, however those anatomical and hormonal differences that do exist are enough to mean that there are some big considerations that need to be taken, which result in little tweaks as well as additions to a training program for a female, that wouldn’t exist – or at least wouldn’t exist to the same extent – in the program of a male in the equivalent sport.

So what are the most important things to be aware of as a female preparing for football, and what does this mean in terms of what you should be looking to do in your preparation?

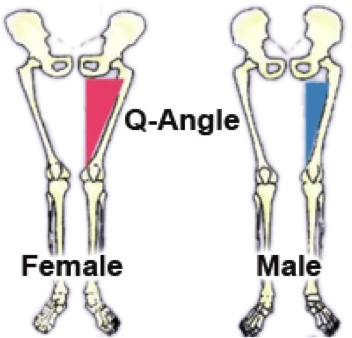

Q-Angle and its effect on the lower extremities

Females have a wider pelvis than males, in order to support child bearing. Of course the extent to which this is the case varies from female to female, in that some women will have much wider hips, whilst others will have more narrow hips. But even the females who have more narrow hips, will still normally have hips that are wider than their average male counterparts (relative to their own respective body sizes.)

This wider pelvis creates a larger ‘Q angle’, which is the angle at which the femur (upper leg bone) meets the tibia (lower leg.) The ‘Q’ stands for quadriceps for those who are interested.

Increased Q angle is well correlated with increased incidence of orthopedic dysfunction such as femoral anteversion (which is a fancy way of saying the neck of the femur leans forward in respect to the rest of the femur) which as a result leads the rest of the leg to rotate internally (knee and foot twist inwards) which further leads to dysfunction at the foot in over-pronation.

‘ACL injury rates are far greater in women – between 2 and 10 times greater depending on the sport.’

‘Such differences in ACL injury rates are not apparent prior to puberty.’

Paul Gamble

Now of course, we can’t change structural anatomy – that goes without saying. However, what we can and must do, is work to strengthen key areas which assist in control and stability of this structure, (we will get to that) with strategies and exercises that have a proven track-record of achieving this. Not only that, but also eliminating poor habits which exacerbate the problem further (such as excessive use of machine based training and un-balanced exercise programs aimed at aesthetics rather than function) will further contribute to achieving this goal.

Flexibility Issues (or is it Joint Laxity?)

When seeing ‘flexibility issues’ listed as a problem, it normally means a lack of flexibility, or an imbalance where one side of the body is more flexible than the other. However, females are generally seen to be more flexible than their male counterparts. I say ‘seen to’ as it is not necessarily more flexible muscles that lead to this perceived greater flexibility, but rather joint laxity. That is, often times, this increased range of motion often comes from more give in the joints, rather than the muscle tissue itself.

‘I have found that female athletes are no more flexible than male athletes in similar sports. Our elite women’s ice hockey players suffer from the same tightness in the hips that our men do. Our elite female soccer players are not significantly more flexible than their male counterparts. Athletes develop tightness and inflexibility based on the repetitive patterns of their sports, not on sex.’

Mike Boyle

As a result of hormonal differences, females have higher incidence of joint laxity, which predisposes them to injury of that particular joint, and the surrounding soft tissue. For this reason, stability of joints – or more specifically training and ensuring stability of joints – must have a premium placed on it when conditioning for footy as a female. For this same reason it is important to be conscious to not overdo it with stretching, as this can be making an already loose joint looser.

Stabiliser Weakness

Closely related and tied in together with the previous point is the stabiliser weakness, or to be more accurate, higher rates of stabiliser weakness associated with females in comparison to males. Whilst this stabiliser weakness is something that is important to strengthen in all females ideally, it is only when participating in high impact athletic events such as a game of footy, that this lack of stability will really show up and have negative consequences if it isn’t worked on.

‘Because of the architecture of a female, such as a wider pelvis, they need more stabiliser strength.’

Paul Chek

In fact, a lack of stability acts like a ‘multiplier’ if you like – where we are adding instability on top of the challenges already associated with structure. So with the wider Q-angle, and the potential problems that arise lower down the chain at the knees and ankles as a result, a lack of stability is BOTH a by-product of the wider pelvis AND also an additional contributor to the issues lower down the chain.

‘We have to use exercises that effectively integrate and activate key stabilisers of the muscles of the body, because these are the muscles that maintain the integrity and health of the joints.’

Paul Chek

What we are now referring back to here is the discussion that we have had elsewhere in articles and in more detail in the books on the importance of using exercises that actively train the key stabilisers in and around a joint, rather than just training the prime movers (like basic machine training.) It is important to perform exercises where stabilisers and prime movers work together just as they do in movements in footy (like dumbbell pressing and lunges and other functional movements), however with the stability weakness shown up in many female athletes, it is important to also specifically target these all-important stabilsers with specific exercises engaging them.

Ligament Dominance

Ligament dominance is a point that ties in nicely here following joint stability, with a brief discussion on a particular ligament – the anterior cruciate ligament – and injury to this ligament to follow. In its simplest terms, ligament dominance is exactly as it sounds – the ligaments ‘dominating’ in a task that in reality they shouldn’t be needing to do anywhere near as much work. In other words, ligament dominance occurs when the surrounding musculature around a joint aren’t doing their job to stabilise as well as absorb forces, and so the ligamentous system takes over this role, and picks up the slack so to speak. This problem is of particular relevance to the female footy player, as this ligament dominance is vastly more common in females than males, and is closely linked with ACL injury – which again, is far more common in females than males (which we are coming to next.)

‘With females, in the absence of active muscular stabilisation they are often over-reliant on ligaments to support the lower limb joints.’

Paul Gamble

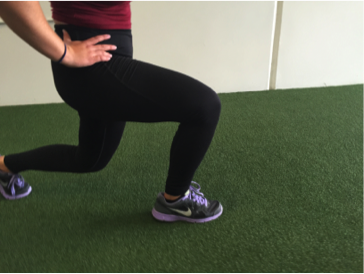

The knees are the best place to illustrate this issue – and indeed are where the most problems in women arise as a result of this ligament dominance. This imbalance results in high knee valgus moments (knees dropping in), and high ground reaction forces in tasks such as landing, pivoting or decelerating.

Given the prevalence of this issue amongst women, and also adding in the high rate of ACL injury, this further highlights the importance of working on this with stability based work, single leg strength, as well as landing based plyometric work in both double and single-leg stances.

Quadriceps Dominance

‘Quadriceps dominance is defined as an imbalance in strength, recruitment, and coordination between the knee extensors and knee flexors. Decreased hamstring strength relative to the quadriceps is implicated as a potential mechanism for increased lower-extremity injuries and potentially ACL injury risk in female athletes.’

Donald A. Chu

‘Quad dominance – the action of the quadriceps can increase anterior shear at the knee joint, and in turn increase the strain on the ACL. This quadriceps-dominant muscle recruitment strategy is therefore potentially injurious to the ACL in female players.’

Paul Gamble

In other words – or more simplified terms, quad dominance is a relative imbalance in work between the quadriceps down the front of the leg, and the hamstrings and glutes down the back of the leg, during various movements. This problem is far more common in women than in men, and is believed to be a strong contributor to not only knee pain, but also knee injury. As a result, a strong focus in training should be given to posterior chain development – both single-leg and double-leg.

Upper Body Strength

Upper body strength is something that isn’t a problem for men – even the ones who don’t have it naturally will have no problem being told to train to develop it. The problem is many go about it the wrong ways and develop muscle imbalance and more injury as a result, as we have just discussed. For most women however, the natural upper body size and strength doesn’t exist to the same level as men naturally, and furthermore, often find it difficult to work on upper body strength often simply due to a fear of ‘bulking up’ which is a myth we will debunk in a second.

‘Since the upper body strength of women tends to be less than that of men, emphasising development of the upper body is important for females who play sports that require upper body strength and power.’

Avery D Faigenbaum EdD

Age and Sex Related differences and their implications for resistance exercise

Since upper body strength is something that does not come as naturally to women, it is at least as important to develop as it is in men, and in reality, even more important to work on developing for females participating in footy, taking into consideration this lack of natural upper body strength, as well as the large amount of upper body work in footy. Not only that, it should be worked on regularly and consistently.

‘Females must strength train more often and continue throughout the competitive season because the drop off in strength is more dramatic when strength training is stopped.’

Tudor Bompa

‘Females, because of lower muscle mass and lower testosterone levels, must have a strength component in all blocks of training, including peak competition.’

Vern Gambetta

So upper body strength is a key focus for female players – given that it does not come anywhere near as naturally as it does to men, and given the upper body requirements in footy. But I must re-emphasise, this strength must be built on top of a sound platform of stability – which we have already touched on.

You will not ‘bulk up’

This is a key concern for many females when looking to get into shape and/or lose weight and they are instructed to begin to perform weight training amongst the exercise they do. Many women stay away from this form of training out of fear of this ‘bulking up.’ For athletes this concern is far less common, given that their goals are performance based much more so than body-composition based, however that does not mean that these concerns don’t still exist to some extent amongst female sportspeople.

In short, females have far less capacity to build muscle size than males do. This is part of why even strength gains (not size) in females are so hard earned and take a lot of consistent work. For starters, females have a greater ratio of slow twitch to fast twitch muscle fibers than men do. You will remember from our discussion in section 1 that the slow twitch muscle fibers are the ones which have a far lesser capacity to grow large and powerful. On top of this, testosterone levels (testosterone is a key hormone in the development of muscle mass) are far greater in men than women. In fact, men have up to 10 times the amount of testosterone that women do.

As David Epstein points out so well in The Sports Gene;

‘Men pack more muscle fibers into any given space in the body and have 80% more muscle mass in their upper body than women, and 50% more in their legs. As far as upper body strength, this translates to a thee-standard-deviation difference in strength. Of 1000 men off the street, 997 would have a stronger upper body than the average woman.’

Still a little worried, then don’t just take our word for it, have a read of the thoughts of arguably the worlds most famous strength coach, Charles Poliquin, on this issue.

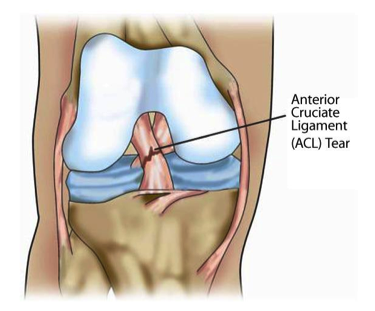

ACL injury in Females

Ok, this one is the ‘elephant in the room’ so to speak. In fact it is probably getting a little boring now – as we hear about this one over and over again. And indeed we have discussed this elsewhere, and do go into it in a lot more detail in Female Specific Strength & Power Training for Aussie Rules, and so will only briefly touch on it here. However, the structural and anatomical differences (as well as a little contribution from hormonal differences) that exist between males and females, and the effect that they can potentially have are no better illustrated than in the incidence of ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) injuries, which are far more prevalent in female athletes than they are in male athletes.

‘The improved ability to handle body weight and control the body is crucial in the prevention of injuries, especially in the lower extremity.’

‘Female athletes are usually deficient in strength for a number of reasons. Therefore there is room for improvement – a huge upside.’

Vern Gambetta

Paul Gamble also discusses in Strength & Conditioning for Team Sports that ACL ligament sprains are the second most prevalent injury in footy behind hamstring injuries. He also highlights the large body of statistics that identify the great majority of these ACL injuries as being non-contact in nature. So when you combine this being a common injury in footy, together with it being far more common in women’s sport than in men’s, and the fact that these statistics that already show a high incidence of this injury are men’s statistics – it isn’t too far a stretch to say that these injuries will become a lot more common as women’s footy grows, unless more is done to prevent it. And specific functional conditioning can certainly play a strong role in achieving this.

A key approach to this problem that is seemingly universal amongst the coaches and conditioning specialists is to perform certain strength and specific neurological exercises as often as possible in the conditioning program. Most advocate for certain things to be done daily, however a more realistic expectation is for at the very least, these things to be done in each strength training session, and then hopefully on top of that, club coaches out there are savvy enough to include similar things in their active warm up prior to club training.

‘Women are certainly more susceptible to certain injuries, specifically ACL tears; this demands that prevention programs be incorporated in daily training.’

‘There is no need to make things complex. The interplay between all the training variables will take care of the training complexity. A few simple drills or exercises properly combined can have a significant training effect.'

Vern Gambetta

So strength training, and specifically targeted strength training is a key for female footy players to reduce the incidence of this very common injury. Mike Boyle gives a very short overview and simplification of the approach that he takes with his athletes in regards to conditioning to avoid ACL issues;

‘A sound ACL injury prevention program needs to focus on two things:

- Single-leg strength

- Landing and deceleration skills’ (plyo)

‘Single-leg strength exercises, a proper plyometric program, and a conditioning program that emphasises changes of direction go a long way to the prevention of ACL injuries.’

‘The key to understanding functional anatomy is to realise everything changes when you stand on one leg.’

So 2 keys to the strategy are highlighted by Mike here; single leg based training, as well as landing and deceleration based plyometric work. The single-leg based training prescription by Mike here highlights an example of the functionality discussion that we have had elsewhere about single leg training in comparison to double leg based training, in that not only are the majority of movements in footy conducted by pushing off 1 leg rather than 2, but also when training single leg exercises, you are also training the key stabilisers of the hip which are forced to do a lot more work, rather than the relative minimal amount of work they are required to do in a double leg setting. This hip stability is a key to develop, as stable hips will mean a lot less pressure gets passed on further down the chain (to the knees and ankles), and there will also be more control as a bonus.

Just in case you weren’t clear on just how highly this world renowned American college strength and conditioning expert rates single leg training and its importance;

‘I truly believe single-leg training is the best way to prevent knee injuries and the best way to train around bad backs.’

‘Single leg strength and stability is the essence of lower body strength, and is the most important quality in performance training.’

‘The importance of this training cannot be overstated.’

Mike Boyle

Mike also makes reference to another key topic of functionality that we discussed in section 1 of this book;

‘The lack of improvement in issues with knee problems lies in the modern sagittal-plane dominant, double-leg-oriented strength training so prevalent in the American training system.’

‘Its clear the key to solving anterior knee pain lies in control of hip, knee and foot movement in the frontal plane, and single leg exercises must be employed in both strength training and power training to address these issues.’

Mike is certainly not alone here, Paul Chek is just one of many who agrees and highlights that;

‘Most orthopedic injuries happen by destabilisation in the frontal and transverse planes, yet we spend 98% of the time training the sagittal plane!’

So from this short discussion and looking at the opinions of various experts, we can take home that when looking to train to minimise ACL injury, it is important that we;

- Train single leg exercises

- Train landing and deceleration plyometrics

- Perform frontal and transverse exercises as much as possible to go with the overwhelming number of sagittal movements that exist in most strength training programs.

I know I said that this discussion about ACL would only be short, but it is so easy to branch off into other areas when discussing it, as they are all linked. Having said that, we are only scratching the surface, and do go into greater detail in Female Specific Strength & Power Training for Aussie Rules.

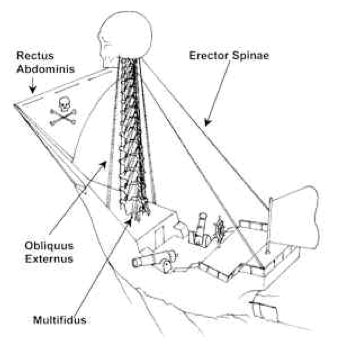

Core/Mid Section

'There is a strong link between an athletes core stability, her hip strength and power, and her ability to modulate high loads during plyometric activities.'

Donald A. Chu

So like we discuss elsewhere, we have the inner unit consisting of the transverse abdominus, the multifidus, the pelvic floor and the diaphragm. This inner unit is concerned primarily with providing stability in the mid section/lower back region, in order for the larger muscles on the outside to have a solid platform or foundation to fire from. This is important again, not only from an injury prevention point of view, but also a high performance point of view. In trying to visualise what I am saying here, I really like the analogy used by Paul Chek in Scientific Core Conditioning, where he compares the inner unit muscles to the small guy wires on a ship;

‘Although the large guy wires (outer unit muscles) support the mast of the pirate ship, its functionality is completely dependent upon the support provided by the small guy wires. These small guy wires represent the multifidus and inner unit muscles in this analogy.’

I think this analogy used by Paul provides a good picture of what I am trying to say regarding this inner unit being important not so much for movement itself, but rather to provide adequate stability and support so that movement can be performed on top of this to a higher level of performance, and without the risk of injury.

In order to get the inner unit activated and firing functionally, it helps to isolate it first with specific isolation exercises, and then integrate this core function into functional full body patterns. This is exactly what we do in the program section of Female Specific Strength & Power Training for Aussie Rules – and explains why certain inner unit exercises are included such as the 4-point variations, when you may question what exactly you are doing them for.

‘At certain times, certain muscle groups – notably deep abdominals, hip abductors and scapula stabilisers – need to be isolated to improve their function.’

‘Without retraining the transverse abdominus and multifidus, the recurrence of back pain is almost guaranteed.’

Mike Boyle

When correctly conditioned, a functional inner unit will fire and provide support during any movement when support is required. So for example, when picking up a weight off the floor, the brain automatically activates the inner unit, which draws in the transverse abdominus and the multifidus. When this happens there is a simultaneous activation of the diaphragm and the pelvic floor as a result of the tightening of the thoracolumbar fascia. Together this provides stiffness in the mid section, and stabilises the joints of the pelvis, spine and rib cage, allowing effective force transfer from the leg musculature, trunk and prime movers of the back and arms to the weight on the floor as you pick it up.

‘Core training will lay the foundation for strength, power, speed and agility training.’

Gray Cook

Sorry about some of the technical terms and boring anatomy, but the take home point is – we occasionally isolate this key section in order to awaken and specifically target it and as a result, condition it effectively, so that it can effectively support and stabilise the mid section, to not only avoid injury in the mid section, but also avoid injury lower down the chain and also enhance performance in larger movements.

‘In addition to injuries directly involving the spine, lumbopelvic stability has implications for injury risk and function of the joints of the lower extremity.’

Paul Gamble

Paul’s last point has particular relevance to all of the topics that we have covered regarding the lower extremity. In short, focused core work to isolate the inner unit, then followed with compound full body based core work to integrate the stability into movement is an important component in countering the issues we have covered, and reducing the incidences of injury in matches.

The use of Plyometrics

Given the nature of certain issues that are more prevalent in females, or in some cases exclusive to females (ACL injury, joint laxity, quad dominance, limb control, wider Q-angle), plyometric based work should make up a vital component of a conditioning program for females from day one. This plyometric training is not all the advanced forms of high impact jumping that you may imagine when you think of plyometrics, but rather begins at fairly low-level/ low-impact exercises aimed largely at landing mechanics and control, that are then progressed.

‘Plyo’s enhance power, but they are also one of the greatest protectors an athlete can have. Elasticity helps you withstand the rapid loads and lengthening of muscle tissue that happens on every stride and play of your sport.’

‘Elasticity gives athletes a set of involuntary brakes and deceleration mechanisms to withstand these high and rapid stretch loads so that the body doesn’t disassemble.’

Mark Verstegen

‘Eccentric strengthening exercises in particular may be important for hamstring strain injury prevention, especially for those with prior history of hamstring injury.’

Paul Gamble

So when we are talking about plyometric work, we are not talking about jumping (pardon the pun) straight into high level and high impact plyometrics – but rather starting with lower level plyometrics aimed largely at learning proper landing mechanics firstly in a double-leg stance, then a single leg stance. This training ties in well with single leg training – so that we are strengthening hip stabilisers, core muscles, as well as the control of the lower limbs.

As mentioned, plyometric work is an important part of appropriate functional conditioning, that ties in with targeting hip stability, core control and posterior strength in order to reduce injury as well as enhance performance. Hopefully you can see the way that these various elements are interrelated and closely linked together, just from a few of the comments made by various experts and coaches;

‘If the athlete doesn’t have the ability to adequetly activate the trunk and hip stabilisers, increased lateral trunk positions will incite high forces that push knees together.’

Donald A. Chu

‘The tendency to land in a knock-knee position during plyometric activities and sports performance is most common in females and is highly related to their risk of knee injury.’

Vern Gambetta

‘Two major contributing factors to poor lower limb control in plyometric activity such as landing are the manner in which the quadriceps, hamstring, and gluteus muscle groups interact and the ability of these muscle groups to maintain proper knee alignment during plyometric tasks. In males, the posterior chain muscle group may more effectively prevent forward translation of the tibia and more neutral knee alignment than in females.’

Donald A. Chu

‘There is a strong linkage between an athletes core stability, her hip strength and power, and her ability to modulate high loads during plyometric activity.’

Mike Boyle

‘Reduced neuromuscular control of the lower extremity during sport movements causes excessive side to side and rotation knee loads during plyometric activities; this increases the risk of ACL injury in females. Specifically, females who land in a knock-knee position (knees dropping in) during jump landing tasks are at high risk of ACL injury.’

Tudor Bompa

Conditioning Young Athletes

So plyometric training is another vital component of a female training program for football, that ties in together with the core work and single leg training and posterior chain development, rather than something separate that is added on as a bonus to create power. Think more of this type of plyometric work as being about developing control of the limbs and joints in the lower half of the body, together with working on joint stability and single limb strength and control.

‘Certain populations have been identified as having a particular need for corrective neuromuscular training. Female athletes warrant particular attention and neuromuscular training should be considered a priority.’

Paul Gamble

In Review

We have covered a fair few things in a pretty short space of time, but they are all related, and many of them can be targeted with the same forms of training and exercises.

But in review, the key areas that we have covered are;

- Upper body strength – or the general lack there of it.

- The Q-Angle, and the resulting issues that can arise here.

- Joint laxity, as well as ligament dominance resulting from a lack of muscular strength and control.

- Stabiliser weakness around the joints – particularly around the hips.

- Quad dominance.

- A high incidence of ACL injury.

And the important things to include in your training program to work on these;

- A strong emphasis on single leg strength, as well as plyometric work, beginning with basic landing exercises, and then progressively increasing the difficulty.

- Isolating the inner unit and pelvic floor, and then integrating it into harder and heavier exercises.

- A lot of work on the hip stabilisers, which in turn will benefit the issues further down the chain. Shoulder stability also gets considerable attention.

- Strong emphasis on the posterior chain – particularly the glutes and hamstrings, and importantly, often in a single leg stance.

- Training movement and stability in all 3 planes, rather than just the over-trained and under-injured sagittal plane.

- Upper body strength work – without the fear of bulking up.

Sounds like a lot, but the reality is that it is no where near as time consuming or confusing as it may seem on paper once you have that plan in place. We cover these areas and more in Female Specific Strength & Power Training for Aussie Rules, including actual periodised programming for 3 difficulty levels. Alternatively, stay tuned to the article section, which is always updated with more and more free information.

Don’t attack next season without a plan. Get your plan in place, program for it, maintain consistency, and don’t lose sight over what you are training for in the first place – to improve your body for your sport.

If you would like more detailed and personalised direction, checkout our personalised online programming, or if you would prefer even more personalised and detailed in-person coaching (for those lucky enough to live in the beautiful city of Adelaide), check out our Athletic Development Coaching and Junior Athletic Development Coaching.

Strength Coach