The REAL problem with ACL injuries in female footballers (Part 2)

Strength & Conditioning Coach - Jaye Edmunds

In case you missed it, in part 1 I highlighted the ACL epidemic that is plaguing our female footballers. As a result many experts are throwing around opinions as to why this may be the case. From the evidence I provided in part 1, ACL injuries are highly preventable with good training. The problem is very few girls are actually doing it, and it’s due to a lack of education around the topic.

What I’ve found is, although there may be many credible sources out there highlighting the benefits that a neuromuscular training program can have on reducing these ACL injuries. Very few actually provide you with the practical tools to implement them. I’ve always been told identifying a problem without a solution is meaningless.

This is why in part 2 i’m going to provide the principles in which a junior football team can incorporate to maximise athletic development and reduce injuries without the guess work.

Although this is not the only way of doing it, it’s a method that covers a lot of bases in a suboptimal environment. What is theoretical isn't always practical. There are many factors that are going to influence a session such as time and equipment allocated to the coach. This is why the methods I will be using will require basically no equipment and will be extremely time efficient.

If the coach has 15 minutes at the start of the session to warm up his athletes (which all do) then they have time to incorporate the methods i’m going to provide below. Is this perfect? nope. Satisfiable? Heck yes.

Let’s begin.

Graeme Morris stated “No component of the session is more guilty for junk programming than the warm up” If we only have 60 minutes per session 1-2x per week and a large component of this is going to go to skills, then we need to be utilising our time effectively.

Because of this there are five aspects I look at when implementing the warm up with a group of junior athletes.

- Is the warm up structured?

- Is it time efficient?

- Does it develop performance in the long term?

- Is it engaging?

- Does it provide a flow on effect to the next component of the session?

If the answer isn’t yes to these above questions then we need to rethink what we are trying to achieve.

Coaches need to start viewing the warm up as an opportunity for these kids to develop skills, not just something that is thrown together for the sake of it. Let's say that you use the methods I will outline below which constitutes approximately 15-20 minutes per session. If your team trains twice per week for 24 weeks that equals 960 minutes or 16 hours of opportunity to get better. 16 hours of quality work is going to have exponential effects on these kids development. To get better at something you must practice it regularly. Throwing in a drill every 4-6 weeks will not not improve skills.

One of the best ways to attack the warm up if you don’t know where to start is to follow a simple acronym RAMP which was developed by Ian Jeffreys (1)

Raise

Activate

Mobilise

Potentiate

I am yet to find a better method that fully prepares the athlete for the session ahead then the RAMP warm up. The RAMP warm up is time efficient, engaging, has a progressive flow and allows for long term skill acquisition. But more importantly it gives structure for coaches to build upon the main components of the session.

Raise

The first component of the warm up is the raise component. The purpose of this phase is to increase core temperature, muscle elasticity, oxygen delivery to the muscles and many more. Unfortunately many go about this the wrong way.

An extremely common method is for the athletes to run 1-2 laps at the start of the session. Although this may get an athlete ‘warm’ does it tick off our five critical boxes?

Is the raise component structured? No

Is it time efficient? No

Does it develop long term skills? No

Is it engaging and requires them to think? No

Does it have a flow on effect to the next component? Arguably no

By looking at the above criteria we have essentially wasted the first 5 minutes of the training session. Although there are many ways to go about this, and coaches should be encouraged to get creative in doing so, I normally approach the raise component in two blocks which constitute no more than 5 minutes combined. I usually begin the session with some general running patterns before implementing some specific running mechanic drills to provide context for the session ahead. These usually come in the form of A series drills. All my drills are either specific strength, hip, trunk & foot strike orientation drills. This is the biggest thing I have seen my athletes struggle to execute and which I see as having the greatest return on time invested. Shoutout to Nathan Kiely’s simpli faster article for this method (2).

They are as followed

- A march

- A skip

- A pop

- A run

- Skip for height or bound for distance

- Prime times depending on emphasis of the session.

These exercises can be found below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uQSVxwO17Y4

All exercises are done for 10m before a 10m run through at building pace eg (60,70,80,90%) Within these specific drills you can add competitions to see which groups are doing the drills the best. Wherever we can get engagement and competition the greater the buy in from the athletes.

With a junior group I would probably initially focus only on one exercise at a time for multiple reps until competency is developed. Trying to add in all six exercises at one will impede learning.

For the second component of the raise warm up I like to add a bit of fun and engagement. Generally this aspect will involve a cognitive and decision making component. Once again the options are endless but here are a few little games you can implement below.

Head, shoulders, knees & cone - I don’t know the exact name of this drill so you can watch the video below for an example. However it teaches a strong athletic base position, requires decision making as well as reaction time. An added bonus is the kids find it really fun.

Knee tag - this game can be a progression from the one above. Essentially you set up a square that could be anywhere from 3x3m to 5x5m and get each athlete to try and tag the opponents knee for a point. Knee tag encourages a strong athletic base, has a cognitive element & teaches a lunge deceleration position.

Keepings off football - An oldie but a goodie. The positive with this one is you start to incorporate the footballs into the warm up. Whenever we can get the footballs involved the better. Coaches can get creative with these drills, however for the sake of this context I would only incorporate handball games until athletes are fully warm.

These activities can be found in the hyperlink below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zqajs1MB8To

Activate & Mobilise

The next critical phase of our warm up is to activate and mobilise our joints. Now that the kids are warm we can start to work through greater ranges of motion and control movement around key joints (stability)

I generally like to combine the two phases together which tends to make the session flow a bit better. The problem we see with most clubs is there go to method to achieve this is through static stretching. Not only does static stretching not really tick off any of our five boxes we need for a successful warm up, but it’s also been shown to have negative effects on power & speed development pre training (3).

Instead I like to implement our key fundamental movement patterns within this section. For those that are unfamiliar, our key fundamental movement patterns are:

Squat

Hinge

Lunge

Push

Pull

brace

rotate

These are all critical movements that set up the foundation in developing strong robust athletes.

With the rise of social media we are seeing our junior athletes slowly becoming less and less competent in regards to our basic fundamental movement skills. From my experience coaching, the majority of kids don’t move overly well, this is why this phase is critical to enhance movement capabilities and help protect against overuse and soft tissue injuries from a young age.

The warm up is the perfect time to implement these patterns while the athlete is fresh and ready to go. Fatigue is a terrible environment for skill acquisition so let’s avoid this as much as possible in these beginning stages. 1-2 sets of 8-10 repetitions is all that may permit, but this accumulation of repetition over the course of the season is going to have profound benefits. Although this is far from perfect, as these kids should be enrolled in a properly supervised Strength & Conditioning program, it’s a great starting point as it teaches bodyweight before external resistance.

Like anything though, give the kids a challenge and progress the exercises throughout the season as the kids become more competent. Some examples could be:

Progress a split squat into a forward lunge into a walking lunge.

Progress a Glute bridge to a B stance Glute bridge to a Single Leg Glute bridge.

To make sure we are hitting our time efficiency aspect, I like to set a timer for the kids to complete the exercises. I like to set 10 exercises done in less than 5 minutes. This helps keep the kids engaged in the process. In saying that, until the kids are competent with all the key exercises the longer the better.

The Mobilise and activation exercises can be found in the hyperlink below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wuJVJy9rOq0

Potentiate

The potentiation phase is the final part of the warm up which provides one of the most powerful tools for the development of key fitness components and overall athleticism. The previous phases of the warm up have set us up to be able to perform at our best. Because of this, failing to include a potentiation phase will preclude peak performance. The potentiation phase needs to be an integral part of any warm-up, as it prepares the athlete for high intensity activity. Not only this, but the potentiation phase is the most important phase when it comes to long term athletic development and skill acquisition. ACL injuries happen in high intensity dynamic tasks. Without teaching these girls how to tolerate these large forces in a controlled environment we are setting them up for failure in competition.

Despite being arguably the most important phase of the warm up, the majority of football teams will skip this phase altogether and jump straight to lane work. I can’t express how much of a bad idea this is, as a critical opportunity to develop technique and qualities such as power, speed & agility will be missed.

When it comes to potentiating the nervous system the categories below is what we are going to implement.

Sprint

Jump

Throw

The benefit of these three categories is they all maximise power production due to projecting into free space. This in turn is going to maximise Rate of Force Development (RFD) , critical for a footballer.

Depending on the time dedicated to the session will dictate how many of these methods you use. For example if you are training two times per week, perhaps on day one you might focus on jumping and landing. Day two might focus on sprinting with an emphasis on deceleration & change of direction. If you only train once per week then you probably need to hit both in the same session. I can’t stress enough, we need to develop savage competency in these above exercises within both controlled and chaotic environments.

Jumping and landing

Teaching the girls to jump and land safely and efficiently is critical to preventing injuries. We know inefficient landing mechanics is a major mechanism behind ACL ruptures hence it needs to be taught. We need to encourage strong positioning of the hip, knee and ankle as we want to prevent any dynamic valgus and excessive hyperextension which can be found in the photo below.

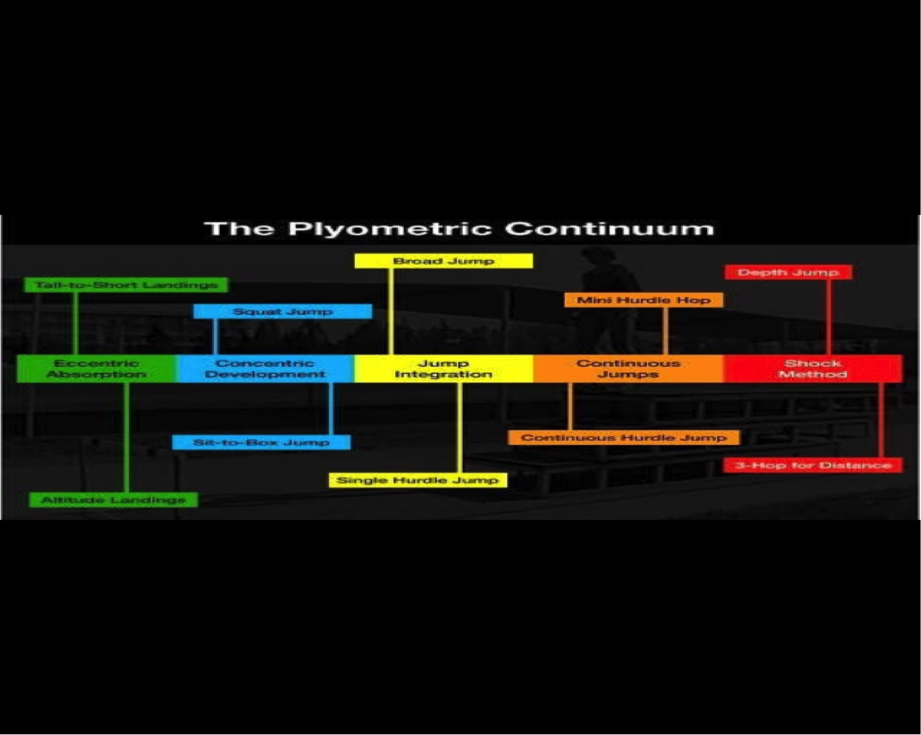

Another important factor to note when implementing jumping and landing exercises is it’s important to utilise multiple force vectors and both single and double leg variations when programming. Quite often most injuries happen in multiple planes of motion and on one leg, so training different force vectors such as vertical, horizontal, lateral & rotational are critical to developing robust athletes. Lachlan Wilmot provided a fantastic continuum that progresses from low intensity force absorption based exercises, to high intensity shock methods. A strong emphasis should be on teaching athletes how to absorb forces and learning to land before they jump. An analogy I like to use is you wouldn’t get a pilot to fly a plane if they didn’t know how to land. The same applies with our jumping and landing progressions. Although these girls should predominantly be in the first 1-3 stages.

Some jumping and landing progressions can be found below:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N4fUoiqiVkI

Acceleration, deceleration & change of direction

On the football field a footballer will perform hundreds of accelerations, decelerations and change of directions. This is why it is critical we spend time refining technique as inefficient movement patterns can lead to injury.

When programming deceleration and change of direction it is important to include a combination of closed and open drills. When I mean closed drills I mean they are pre planned and don’t require a decision making component. An example of this could be running to a cone and performing a ‘cut’. The movement is predetermined.

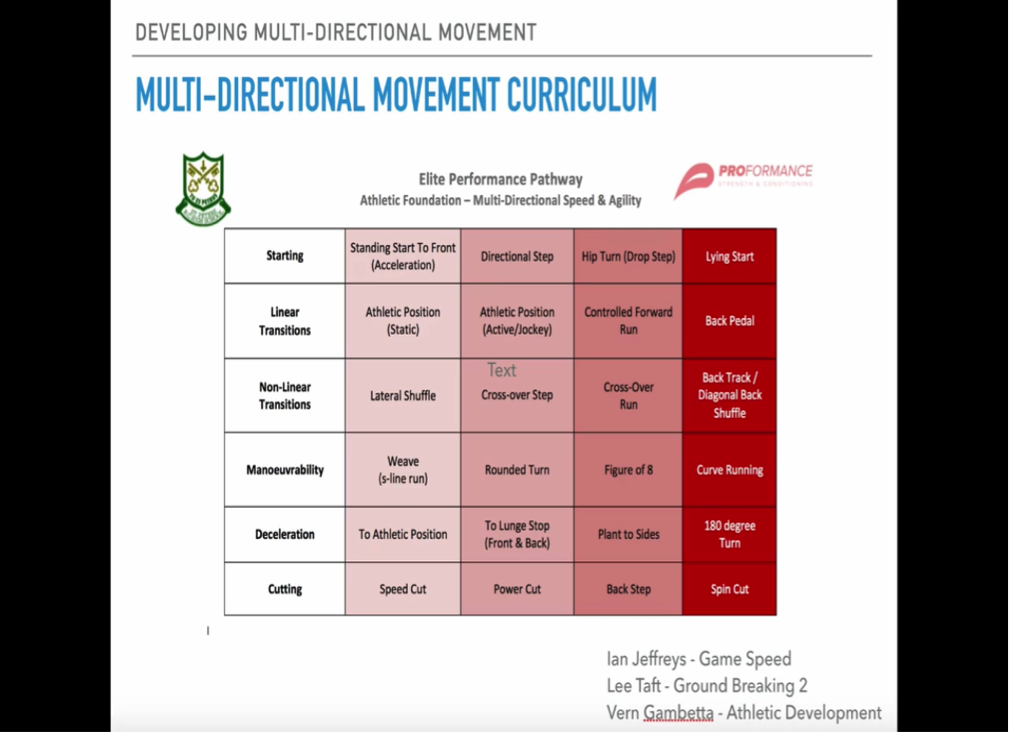

Open drills on the other hand are often reactive and require many different external stimuli to complete the movement. This is what we often see in a game. However if you can’t perform basic change of direction movements in a closed environment then you are going to struggle to implement them in a chaotic environment. Because of this I would recommend spending time developing technique in non competitive closed environments before moving to more open chaotic drills. I do like to add in some competition amongst peers as it promotes engagement within training. As a rule of thumb though, keep training consistent with steady progression and build exposure to a wide variety of movements. The proformance community provided a fantastic resource on all the different multi-directional movements that need to be taught. I go over some of these in the video below

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KbIlSyohkQ8

So there you have it. In under 20 minutes we have prepared the athletes to train, we have developed long term skills, and we have kept the footballs involved as much as possible. On top of this they still have 45-60 minutes to develop conditioning, technical football skills and any extras if need be

If you have any questions in regards to any of the information in both part 1 & 2, feel free to contact me on the social media platforms below.

Jaye Edmunds is a Strength & Conditioning coach at Woodford Sport Science Consulting. He is currently finishing up his double degree in Secondary Teaching & Exercise Science. Jaye has worked with a variety of both male and female footballers ranging from VFL to junior level football.

He is currently the head Strength & Conditioning coach at the SFNL umpires association.

He can be found on the following social media platforms;

Instagram: @performancecoach_edmunds

Facebook: Jaye Edmunds - Athletic Performance Coach

References

1. Jeffreys, Ian. (2017). RAMP warm-ups: more than simply short-term preparation.. Professional Strength and Conditioning.

2.

https://simplifaster.com/articles/developing-game-breaking-speed/

3. Jeffreys, I (2008) Warm up and Stretching. In: Haff GG and Tripplett T. The Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning (4th Ed) Champaign Il. Human Kinetics. 2008