How fast are football players

A graphic that is becoming more and more prevalent in matches these days is the top speeds measured graphic. I must admit this is certainly a hell of a lot more interesting than the tedious, overdone and completely irrelevant total distance covered graphic that still seems to get a regular run. But what exactly does it tell us about how fast the elite players are?

This is particularly worth considering at this stage in the sporting cycle, with the fastest person on the planet having just been decided in the 100m Olympic final.

So on our little AFL podium, the fastest players clocked over the course of last season were;

- Bradley Hill, 36.6km/h

- Trent McKenzie, 36.4km/h

- Charlie Cameron, 35.6km/h

If interested, the top 5 from each club can be found here.

For a quick comparison, when Usain Bolt set the world record, he was clocked at reaching a maximum speed of 42.72km/h between the 60-80 meter mark of a 100m sprint back in 2009. (Interesting to note the distance that it took for him to reach that speed – 60 meters – and then he only held it for 20 meters. This is relevant to us – we will get to that).

Trent McKenzie perhaps comes as a bit of a surprise, but it is certainly images of players like Charlie Cameron and Brad Hill in full flight that pop into peoples heads when they consider ‘I wonder how these guys would go in an actual sprint race?’ But in reality, how impressive would they be in say for example the 100 meter sprint?

A common figure put across is that most players – even the very fastest – would be very lucky to break 11 seconds – at least with any consistency. For a bit of context, all 6 finishers in the mens Olympic final last night finished under 10 seconds. Running even 11.0 would leave you a good 13 meters behind the guy who came last in the final. Ok these are the freaks of nature who represent the upper limit of the worlds gene pool and train exclusively for this pursuit, so this is perhaps to be expected. 11.0 would have placed you 7th in the Jamaica-owned womens final. Even 1 rung lower – at national competition level, 11.0 wouldn’t get you even close to a national final at senior level (mens), nor a final even through the upper junior age levels.

There are a couple important ‘Buts’ here before moving on.

1.Sprinters train purely to be sprinters, nothing else. They should be much better purely from this fact. Yes correct, nothing more to add. This is part of the point.

2.And closely related to the last point – there is a actually much more to competitive sprinting than just running fast, or just running as fast as possible. Its funny the bemused looks this fact initially gets when you first point it out, but the various technical elements of the different phases in a sprint, which are also influenced by tactics based personal strengths and weaknesses all impact. There are an enormous amount of variables that go into preparing for those 10m seconds.

The follow up question is often then ‘well how fast could the fastest players like Brad Hill actually be if they quit footy and started in 100 meter sprints?’ Certainly consistently quicker over 100 meters than the 11.0 at best, on a good day that would be possible currently. But just how much better, and over what period of time is impossible to ever know – and not relevant to the point of the discussion – which was entirely focused on how fast the quickest player would be if they actually ran such a sprint with their current ability in their current environment, and then how this compares to proper sprinters.

So it is fair to say that although their speed is impressive, it is still a long way behind the best – or even the upper-middle.

So what else does this tell us about speed in our game?

In footy, there are very few opportunities to reach your top speed

It takes approximately (and generally) 5 seconds to reach top speed, slightly less for females, and slightly more for the absolute elite sprinters. This is of course 5 seconds, unimpeded, going as hard as you can, in a straight line – hardly conditions that are met very often in footy. As such, absolute maximum velocity, while interesting to note, and certainly not a bad quality to possess, perhaps isn’t as important as another derivative of sprinting.

Acceleration is more relevant

It’s that speed ‘out of the blocks’ that is far more important in terms of an isolated physiological test or ability that is transferable to match performance. The good news is also that acceleration is less restricted by genetic ability than absolute maximal velocity. An important thing to note is that acceleration in a game is very different to acceleration in a standard sprint. Even aside from needing to respond and react to the changing match around you, accelerations within a game will be performed from rolling starts more so than stationary starts – and additionally, they will occur in different directions, having been initiated from varying positions.

Change of direction, and the ability to get back up to speed quickly is more relevant

Again, closely related to the last point, but the ability to be light on your feet, and change direction while holding speed of movement is also more relevant than straight ahead top speed. There are so many speed and directional changes in a game that being good at this is far more beneficial than being able to run fast in a straight line. Being able to do both won’t hurt, but if you had to have just one, it would be the former.

This has been interestingly tested within the world of soccer (a sport prone to idiocy around the athletic ability of some of it’s players – with at one stage someone claiming to have measured Gareth Bales top speed in a game as higher than Usain Bolts). A few years a go, Christiano Ronaldo was tested against an Olympic sprinter named Angel David Rodriguez (personal best 10.23 in the 100 meters) over 2 tests. The first was a 30 meter sprint, the second was over the same distance, but in a zig-zag pattern. As would be expected, Angel was .3 seconds faster in the standard sprint, however Christiano was quicker by an even bigger margin in the zig-zag pattern.

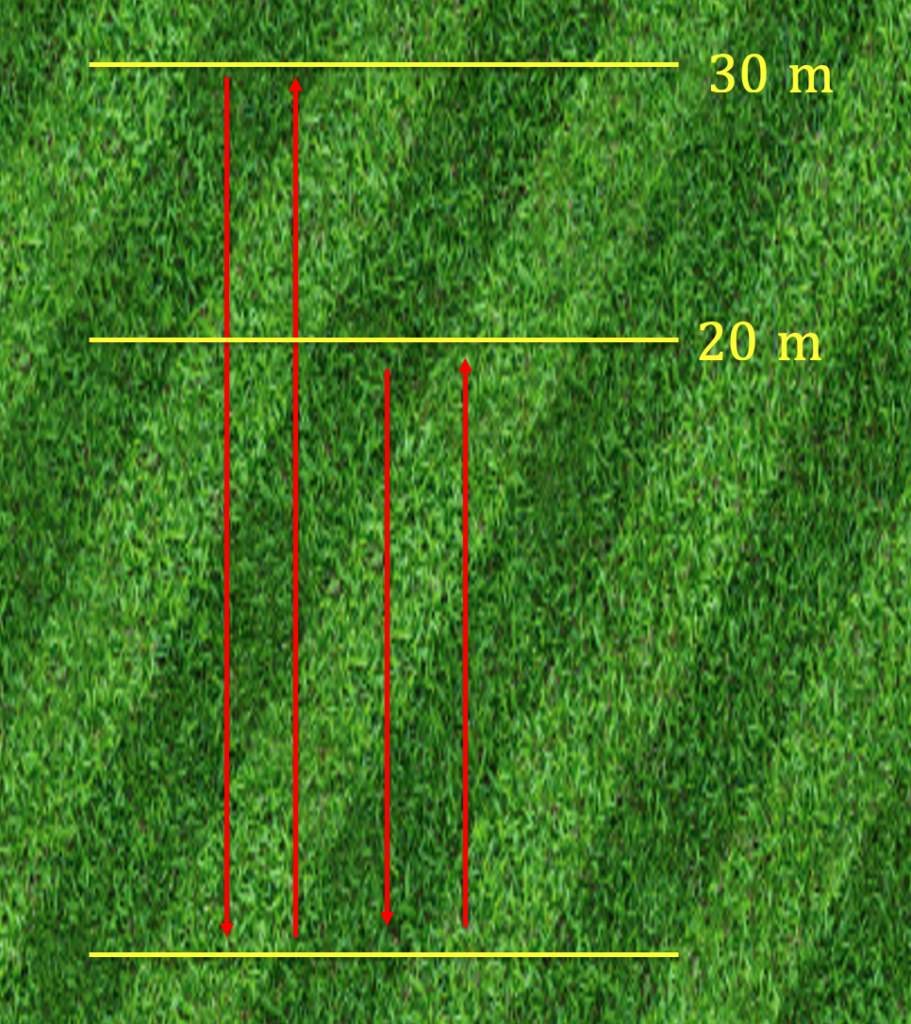

Bringing it back to footy, lets say we take the 100 meter sprint, and turn it into a 20 and 30 meter shuttle sprint, where you must plant your foot across the line before cutting back and returning to the start. So you sprint 20 meters up and back and 30 meters up and back. So the same distance – 100 meters. If we lined Usain Bolt up against Brad Hill or Charlie Cameron in this new race, I would feel very confident both players would not just beat Usain, they would beat him comfortably. Acceleration was never Usain’s strong suit in the 100 meters (remember he reaches top speed at 60 meters), and change of direction would no doubt be even weaker.

It goes without saying that ‘speed’ is only 1 element in footy, and there are other areas to consider. Even related to speed, is game speed, speed of decision making, speed of ball movement, which has much more to do with team cohesion and skill execution than leg speed. But the point of this discussion was to consider where our fastest players would be placed, where they to decided to line up in the starting blocks. And then more importantly, to consider exactly what kind of ‘speed’ we value in footy.

Strength Coach