Bodybuilding training for football – Good or Bad?

We felt this was a very important discussion to have, as it is often controversial (though it shouldn’t be), and full of misunderstandings.

When talking about ‘bodybuilding principles’, this term is very broad, as the sport/activity of bodybuilding encompasses many different variables, and not necessary everything is bad (in terms of athletic preparation for a field sport like football.) It is human nature to like things being ‘black or white’ and easily categorised, where the whole broad term of ‘bodybuilding’ is either good or bad, period. However, this is a little too simplistic, as the real world always has varying degrees of shades of grey. So lets first clarify which bodybuilding principles we tend to mean when mentioning their lack of suitability when strength training for football, and then delve a little deeper into a few of them, and related areas.

Generally when mentioning the lack of suitability, the bodybuilding approach that we are referring to includes;

- Split routines – ‘back and bi’s day, ‘chest and tri’s day’ or ‘arms day’ as well as an occasional ‘legs day.’

- Isolation training dominating – bicep curls, shoulder abductions, leg extensions, tricep pulldowns.

- An emphasis on blasting a particular region to failure on each and every set, and each and every session, with little regard for movement quality.

- Standard bodybuilding rep counts (for example 3-4 sets, 8-12 reps, 45-60 second rests) with limited variability in these – a relatively constant focus on just doing a movement, with little regard for quality and speed changes for example.

- Machine training – machine meaning anything where the weight being lifted moves on a fixed axis – plate loaded or pin loaded machines. (Cable column exercises and even lat pulldowns do not count here, as you have freedom to move and control your own range.)

- Sagittal plane dominance.

- Success judged by the mirror – ‘if I am getting bigger, I am improving.’

Those are the most key points in a quick nutshell. So lets now expand on this discussion.

Why not split the body into parts?

The first ‘red flag’ that this should raise is the fact that by splitting the body up into parts (and days), is the number of days or sessions needed to put together the whole body. Once factoring in club training, as well as perhaps running based sessions on your own if it is pre-season, or matches if it is in-season, where is the time to perform a day for each body part or region?

Additionally, at what stage is there any opportunity for recovery? (After all, it is during the recovery that your body actually improves via ‘super-compensation'.) The mentality is usually ‘my chest and triceps recover while I do my back and biceps.’ However, unfortunately the body isn’t this simple – you can’t just ‘shut down’ certain areas to recover while you work on something else. Ok, with the muscle tissue, you may not be primarily hitting a particular area, but it is still the same nervous system at work, being placed under work, day after day in this split routine approach. And if each and every bodybuilding style session involves pushing the limits of failure, and doing so almost daily due to being broken down into regions, there is very little opportunity for the nervous system to recover.

And this raises another key point in this discussion and that is that the brain recognises movement, not muscles. The following discussion point is an abbreviated discussion taken from Functional Strength Training for Australian Rules Football.

“I do not believe in an arm day nor a leg day. I think ‘basic human movement day.’ Sure, we can break this work into vertical and horizontal and single limb and probably many more options, but generally we need to deal with these each day, and certainly each training session.”

Dan John

The modern fitness industry is so damn focused on muscles (particularly how impressive they look), and all the garbage in magazines is so focused on ‘this exercise for this muscle’, that most people are surprised, even shocked, to hear me say that muscles themselves, are only an afterthought in terms of getting stronger and moving better. And by that, I don’t just mean that the look of muscles is an afterthought when training for athleticism, but rather muscles in general. You see, explaining things in terms of certain muscles used and trained in an exercise is an easy way of getting to understand what areas and functions we are focused on improving, however at the end of the day, the actual muscle tissue on its own is relatively irrelevant to improvement. Muscles are simply sacks of flesh. Muscles are controlled by the nervous system, and the nerve fibers that innervate them, and any developments in strength and coordination and movement are all in fact developments in the nervous system.

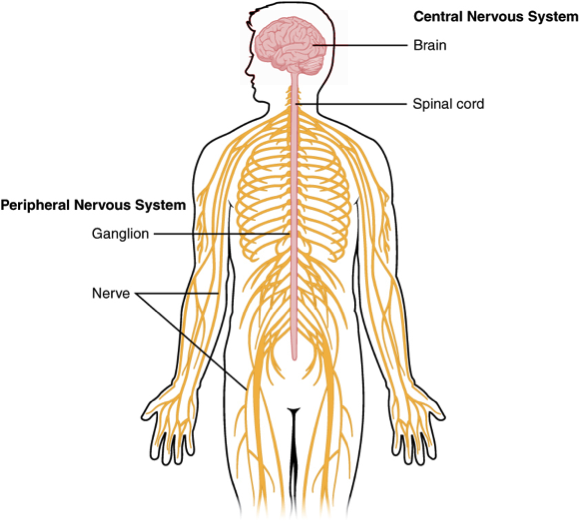

Lets keep this fairly simple and practical. The nervous system when we are referring to exercise consists of the brain, the spinal chord and all the nerves (major and minor fibers) that branch out from it. These are responsible for all movement commands. No movement, be it a quick reflex or a maximal effort contraction of a muscle, occurs without a command being sent from the brain down through the spinal chord out through the nerves to the muscle/s. This is a very broad and simplistic explanation of a very sophisticated process, and indeed there are instances where this process differs, like certain instances for example, where certain reflex actions originate at the spinal chord, rather than the brain. But the key point is that all movement is controlled by this system, muscles have nothing to do with the command, they simply act out the command.

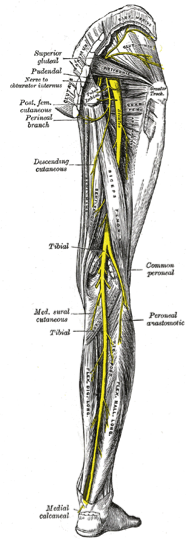

The picture on the left shows the central nervous system consisting of the brain and spinal chord branching out to our peripheral nervous system, consisting of the nerves themselves. The picture on the right shows these nerves and subsequent fibers (the yellow parts) innervating the muscles of the leg. Whenever you run, kick or jump it is this system controlling it, not your muscles, and the quality and power with which you will perform these tasks are determined by the quality of the program in the nervous system, not by the look and size of your muscles.

Following on from this point, the nervous system acts like a ‘living computer software’ program of sorts, where movements are stored in the central nervous system ‘memory’ and refined over time, depending on how they have been developed, and what qualities have been developed. This may be strength, speed, stamina (as a few examples) in any one of a number of unlimited patterns, and they are improved by continuously being trained in specific ways. And so whenever you call on your body to perform a certain task, your central nervous system fires a previously stored program to perform this task, and every time you perform it, you are refining and hopefully (depending on the quality of the movement program you are firing) improving it.

By recognising movement patterns, the nervous system is able to operate a much more quick and efficient system. Just think of how inefficient and slow the body would be if your brain had to consciously think of every single individual muscle involved in each movement in order to perform a task. Even something as simple as walking would be a slow process, let alone complex neural tasks like sprinting, kicking and tackling. Suffice to say, the more complex a task is, the more complex training required to properly prepare the nervous system for the task, and this is a key point to remember when conditioning for footy, because there is no more neurally-challenging sport in terms of all the movements and athletic tasks and challenges on the system required.

So for example, having a big chest from doing hundreds of machine chest presses doesn’t meant that you will be better at pushing off an opponent, just as doing hundreds of bicep curls doesn’t mean that you will be a better tackler. Why? Because this is a muscle focus, rather than a movement focus. These thoughts are a common mistake made as a result of training being so muscle focused. But remember, the brain recognises movement, not muscles.

Yes you use your biceps in a tackle, but you also use them together with your hips, legs and entire torso in any one of a number of patterns. You may like looking at your biceps while you flex them doing a curl, but performing heavier curls and for more and more reps will not transfer over to any use in a game of footy, especially for a task like tackling.

One more important thing to realise here is that muscles have various different functions and roles to play depending on the movement or task being performed, or the particular position or situation that they are in. Textbooks often list a ‘muscle function’ as if it only has one or 2 things to do, however these textbook writers only do this for simplicity purposes when teaching basic anatomy. The fact is, a hamstring may be used as a ‘knee flexor’ (which is how most anatomy textbooks list the function of the hamstrings) in some instances such as kicking a ball, but what are the hamstrings doing on the other leg? Certainly not flexing the knee, but rather being used to both extend the hip as well as assist in proving stability and balance to the hip on the other leg (if all things are functioning as they should.) So you can see a muscle can provide many functions depending on what is needed, and it may be a prime mover in one instance and then function primarily as a stabiliser in another instance (and in all 3 planes of movement remember, not just sagittal as is the case with a basic hamstring curl), and as such, training an individual muscle in an isolated function is useless, as this training will have no use or carryover if that muscle is called upon to do other things as it will be.

This hopefully helps to initiate the understanding of the folly in breaking the body up and blasting different regions, as a means to get stronger for a full body complex sport like footy. A performance-based sport must be attacked with a performance-based mindset. This leads in nicely to another brief point.

Greater chance of a disconnect between training modes

More and more you should be hearing strength and conditioning coaches, or athletic development coaches or high performance coaches discussing the concept or approach of ‘athletic performance’ more so than ‘strength and conditioning’ or ‘fitness’ when it comes to sports like football. The general gist being that ‘athletic development’ better encompasses what these coaches are aiming to achieve with their athletes in their approach. Its not necessarily about making them stronger or making them fitter per se, but rather a greater combined overall ability in the various physical components that are important to the sport – in our case speed, agility, jumping and landing, hamstring integrity and strength, core linkage to the upper body, etc. In fact for anyone interested, here is a great and easy to understand presentation by Port Adelaide high performance manager Ian McKeown discussing just this point, as well as his approach at Port Adelaide.

‘All components of physical performance: strength, power, speed, agility, endurance and flexibility must be developed in a systematic, sequential, and progressive manner to prepare the athlete. Athletic development coaches enhance athletic performance by developing athletes that are completely adaptable and prepared to handle the psychological, physical, technical and tactical demands required to compete.’

Vern Gambetta

‘Trainers who separate strength and its programming requirements from other physiological characteristics of their sport make a mistake that over time may affect their rate of success.’

Tudor Bompa

But the key point here is that with the general bodybuilding approach, given that much of the attitude is about size and split routines rather than certain movement abilities and tasks, it is far easier for there to become a disconnect between various elements of an individuals training program. For example where does the biceps and triceps day fit in with the overall plan? Or how does it contribute to a certain goal? What will occur here is a disconnect between the 2, where the strength based work is seen as separate from running or club training, and the 2 will work to detract from each other, rather than complement each other. Certainly this isn’t unique to bodybuilding style training – however it is far more likely to occur, given than movement patterns and tasks are often forgotten in preference of body parts and regions in bodybuilding, making it much more likely.

Compound Exercises – Leave the isolation as a last resort

Isolation exercises have their place, especially if you need to rehab a particular joint, muscle or body part. And additionally there are other instances where isolating a particular area that requires strengthening or ‘awakening’ prior to other training such as the notoriously lazy glute medius, can have a place. However, by and large this is something that is done to excess with the standard bodybuilding approach (if football is the primary goal – by all means if bodybuilding is why you train in the gym, there is nothing wrong with this isolation, nor is anything else in this article relevant.)

Remember, the brain recognises movements not muscles. By this stage after reading the last couple points, you probably have a good understanding of the main reasons why strength training for footy should be based almost exclusively around compound exercises involving many muscles and muscle groups and almost eliminate all isolation exercises like bicep curls and shoulder abductions. You may love the way your arms look in the mirror when you do them, but if you want to focus fully on training to be a footballer, don’t waste your time doing these, or at least only perform them after all the important functional work that will be of benefit has been completed. Aside from these reasons to drop isolation training and focus on the compound stuff;

- Far more carryover in training adaption relevant to match day

- Training movements not muscles

- Challenging your nervous system more

- Being far more challenging from a work rate and conditioning point of view too.

There is also the added bonus of being far more time efficient with training. You likely work a full time or part time job, or are a student on top of playing footy, and on top of having a family and social life and all the other things that go with everyday life, and do not have the luxury of being a full time professional athlete. And lets not forget the actual club training and match days. So you likely will not have an endless amount of time to dedicate to your strength training program for footy. Therefore it makes sense to pick exercises where you are getting as much work done in as little time as possible. So it should be obvious to want to pick exercises that are achieving the greatest possible result in the limited amount of time that you have at your disposal. Time spent doing bicep curls and tricep-pulldowns and sit-ups is time wasted. You must prioritise – and you will understand exactly how and what very shortly!

One final added benefit of performing compound exercises over the inefficient isolation stuff, as outlined by Tudor Bompa in Periodization Training for Sports, is that these exercises also create a far greater workload for the cardio-respiratory system as well, meaning that you are also getting a lot more ‘cardio’ conditioning when performing these exercises. This benefit of this for training for footy goes without saying.

What about the recruitment and training of deep stabilisers?

This could easily become a very long-winded and technical discussion on anatomy, but I promise I will not let it, and will only quickly go over the most important and relevant essentials. What I am talking about here are all the various muscles inside the body that you don’t see when looking at the mirror, or on the outside of the body. These are all the deep muscles that you wont see bulging when you exercise and these certainly wont be the muscles that those around you are impressed by….simply because they aren’t visible. However, they are no less important than the outer unit muscles responsible for actual movement.

Key Fact: Stability must always precede force generation

These deep stabilisers are responsible for providing for stability in and around across all your joints, in order for the outer unit muscles that are responsible for the actual movement of the body, to have a solid foundation to fire or function from, and to move in the most efficient manner, whilst avoiding injury. To give a good analogy of why this is important, I will take from the work of world-renowned holistic and corrective exercise practitioner Paul Chek. Paul uses the old expression that ‘you cant fire a cannon from a canoe’ when talking about exercise and movement in general. In other words, if you don’t have a solid foundation deep (around the hips, spine, shoulders, ankles, knees, core, etc) then you can’t expect to move or perform efficiently, and certainly cant expect to perform at a high level for very long without injury.

Therefore performing exercises that also require the use of the deep stabiliser muscles is what must be included in a truly functional training program for footy. For example, when doing a pushing exercise, a dumb bell press on a Swiss ball, or a standing cable press are fantastic in this sense, as you will not just be using the obvious outer unit muscles (pecs, triceps and anterior deltoids), but will also be firing all the stabilisers in and around your shoulder, in order to provide the platform to push from, as well as the stabilisers around the hips, and also the inner unit core muscles. Believe me, you will realise exactly what I mean when you do these exercises….or at least your body will. Whereas on the other hand, a seated chest press on a pin-loaded machine, or even a plate-loaded machine, is useless!..... all you will use are those outer unit muscles (pecs, triceps and anterior deltoids), as you aren’t required to stabilise the weight at all, because the machine is providing all the stability. All you need to do is push.

You could literally do a seated chest press machine exercise with your eyes closed. That is because the machine is your stability system, leaving your key stabilisers with nothing to do. A lying chest press is an enormous improvement that will not only force your stabilisers around your shoulder to fire in proportion to your larger muscles, but also integrate your whole body into the exercise.

This may not seem like a big deal, however over time, as you develop larger ‘outer’ muscles, whilst having not appropriately conditioned the inner stabiliser muscles, what you end up with are large and strong muscles that you are unable to stabilise (as the inner stabilisers have been underdeveloped relative to the outer strength.) You would literally be better of doing no strength work at all, than developing an imbalance between your outer strength and your inner stability. Football is high impact and tough on the body as it is already, don’t go making it even harder on the body by preparing it inappropriately in this manner.

Relative Strength & Power

As touched on earlier in this article, as well as talked about in more detail elsewhere on the site and in the books, bodybuilding aside, when training for football, whilst strength is important, we aren’t necessarily training strength purely for the sake of getting stronger in the traditional sense. It is overall athletic ability that we want to develop, and strengths importance lies in the fact that strength is the underlying quality that these other abilities are built on top of. That is, first we must build our baseline levels of strength in certain movements or patterns, and then on top of that we can develop expressions of power such as speed, acceleration, deceleration, agility, jumping, landing as well as the ability to repeat these to a consistently high quality level throughout a game.

‘Because power production is the key determinant to success in sport, athletes need to use training techniques that are focused on transitioning the strength gained from heavy (but slow) resistance training to high velocity movements.’

Donald A. Chu

"We are very careful about body weight. Our boys are very sensitive to getting too heavy, especially when they’re young – they’re high susceptibility to stress responses, whether it be complete stress fractures, but more commonly little hot spots – just from a sudden increase in load (body weight.) So we are very very careful about how much load we put into them in their first year.

Because at the end of the day they got drafted because they can run all day, I’m not about to pile 6kg onto them in their first year, and suddenly they cant run.

Our target weight is one of our biggest focuses.

Often they all don’t need to be big. We view it as yes we need to get stronger, but that doesn’t always mean we need to get bigger.

Its just efficiency as well at the end of the day. Some of our boys will crack 18km in one game, and of that they might do over 2km of high speed running – which is exceptionally taxing. So if you have got 1.5kg more on you (that you had from training,) I’m sorry but that becomes a load that ultimately you may not be able to handle week after week."

Lachlan Wilmot

GWS Giants

(Now Paramatta High Performance Manager)

Noted. But where does this fit in with the bodybuilding discussion? The key is in understanding the concept of relative power (and relative strength for that matter.) The following discussion is a snipped taken from Advanced Power & Plyometrics for Footy.

In his book Every Day is Game Day, world leading sports and athletic conditioning coach Mark Verstegen discusses a concept that is very relevant to what you are trying to achieve in your conditioning program, and that is relative power. Relative power is basically your power-to-weight ratio. So for example if your body weight goes from 75kg to 70kg, but you maintain the same power and strength, your relative power has gone through the roof.

In the words of Mark Verstegen himself;

‘Relative power makes the most efficient athlete.’

‘Relative power makes things easier for the athlete. He’s able to control that bodyweight and also to efficiently decelerate it and reaccelerate it into the ground or someone else.’

As Mark Versetgen says, ‘There is a misconception that in order to become powerful you need larger muscles or more weight.’

Lets go a little more in-depth into just how Mark looks at relative power as it relates to athletic conditioning, and how it shapes his philosophy on power training. Some coaches in footy would disagree with the following outlook on power but its worth noting from this world leader in athletic conditioning;

‘Lets say we have a guy who weighs 200 pounds and 10% body fat. We measure his performance in the vertical jump and the broad jump (relative power tests.) We then add 10 pounds of lean body mass whilst keeping him at 10% body fat (but he now weights 210 pounds.) We then measure the 2 tests again, and find that his performance has remained the same despite an increase in weight.’

So far nothing too out there, but this is where Mark’s outlook becomes interesting, and perhaps a little different to what you may expect in footy.

‘Most coaches and scientists would see this as a huge positive. After all he was able to gain 10 pounds and still jump as high. I would say we failed. Our expectation with the way that we train for power is that if we add 10 pounds of lean body mass, we expect his vertical jump to improve and for him to become faster.’

Whilst this outlook is very accurate and definitely the case for most non-combative sports (tennis as a good example), the high contact nature of footy still means some size is important, and in certain key positions where extra body size is very useful, such as key forwards, extra size can be quite important, provided that athlete can at least maintain current power output.

However, this is still a very important point to take note of, as if you can take one thing from this it’s that we do not want to get caught up in just adding size for the sake of size. The main focus is improving movement quality, and if there is any addition in size and weight, we want there to be as much improvement as possible in the various expressions of power output, to accompany any increase in size.

World class sprinters have extremely impressive physiques in terms of muscular development. However, unlike bodybuilders and standard gym junkies, these guys muscles are every bit as powerful as they look. The muscular development is an added benefit to the training that they perform, rather than a primary focus. Ensure that every gain in muscle mass that you develop is accompanied by an at least equal development in physical ability.

Once again, this comes back to losing sight of where the strength work fits in the overall picture of what you are trying to achieve. Surely it makes sense that when performing supplementary training for football you are aiming to improve your physical abilities – more explosive takeoff into acceleration, more controlled deceleration, quicker change of direction, etc. So if you are putting on size, you would hope to at the very least be maintaining these and other abilities.

We will say it once again, if football plays second fiddle to bodybuilding for you, then the bodybuilding approach will not be a problem, as football is only an afterthought. Additionally, if you are a little in the middle of the 2, once again, you will not ruin your current playing ability by training in such a way (as is often interpreted). However if you hit the gym with football genuinely being your primary focus from doing this form of training, and you are serious about targeting improvement here, by using these sort of principles or practices (remember its not black and white with ‘bodybuilding’, we only mean certain methods) you will not be maximising the return from your time spent training.

Pre-season starts now.

If you would like more detailed and personalised direction, checkout our personalised online programming, or if you would prefer even more personalised and detailed in-person coaching (for those lucky enough to live in the beautiful city of Adelaide), check out our Athletic Development Coaching and Junior Athletic Development Coaching.

Strength Coach